Counting parasite worm eggs in the faeces from your animals is easy and economical with Vetlab Bespoke FEC starter kits, that include flotation solutions, veterinary quality microscopes and everything you need to carry out Faecal Egg Counts.

Internal parasites of grazing animals spread from one animal to another by infective eggs shed with the faeces of an infected animal. Parasite eggs hatch into the grazing pasture where the active worms spread out and are eaten by grazing animals repeating the cycle of infection and increasing the ‘worm burden’ of all exposed animals.

Worm eggs, passed out in the faeces of infected animals, can lie dormant through the winter to reinfect grazing animals when they return to pasture in the spring. Heavy worm burdens reduce growth rate, cause a loss of weight, body condition and increase vulnerability to infection resulting in emaciation and even death.

What Is A Faecal Egg Count?

A faecal egg count or FEC is a measure of the number of parasite worm eggs in an animal’s faeces (droppings). Results, presented as the number of worm eggs per gram (epg) of faeces, gives an indication of the level of infection or ‘worm burden’ in an individual animal or for the entire herd.

The Faecal Egg Count is a useful, non-invasive method for estimating the individual worm burden of grazing animals including horses, cattle, donkeys, sheep, goats, llamas and alpacas. Owners of a small number of animals may be able to check every individual animal regularly, while larger herds or commercial farms may rely on representative sampling rather than each individual animal.

Why Are Regular Faecal Egg Counts Necessary?

Zero or medically insignificant Faecal Egg Counts will reassure keepers as to the internal health of their animals and to the hygiene and cleanliness of their pasture and stables. Confirming that no medical intervention is necessary will save on costs, and ensure that any veterinary treatment required is targeted where it will bring most benefit.

Medicating animals only when necessary prevents the overuse of drug treatments. In recent years, the ready availability of anti-worm medicines has led to a ‘treat first, test… maybe’ approach by some keepers. Overexposure to unnecessary medication has led to increasing drug resistance in parasitic worms and the growing risk of all available treatments becoming ineffective.

How Often Should An FEC Be Carried Out?

In the UK, Vettimes reports that FEC testing should be performed in all horses at 8-12 week intervals throughout the grazing period (spring to early autumn). Testing should also be carried out at the end of winter if horses have been grazed outdoors frequently or for longer periods.

Alpaca and llama specialists, The British Alpaca Society recommends advice from your veterinarian as permissible levels of FEC may depend on the age/condition of the animal and the type of worm. As a general rule, says BAS-UK, it is common to treat far lower egg counts in alpacas than might be considered in other animals.

For Sheep, the industry led Sustainable Control of Parasites in Sheep (SCOPS) recommends regular FEC testing on a 2 to 4 weekly cycle throughout the grazing season. SCOPS recognises that collecting faecal samples from every animal in a commercial flock isn’t practical!

This SCOPS link tells you how best to get a reliable overview of the parasite burden in a large flock. Collecting fresh droppings from a representative number of animals for professional laboratory or DIY testing is suggested as a testing strategy.

Can I Carry Out Faecal Egg Counts On My Own Animals?

Collecting fresh faecal samples from your horses, cattle, donkeys, sheep, goats, llamas and alpacas is the first step in reliable DIY faecal egg counting. SCOPS recommends wearing gloves to collect faeces less than 1 hour old and washing hands thoroughly afterwards. For large flocks, sampling 10% of the animals is advised.

Samples can be sent to commercial veterinary laboratories for testing but, with a little practice and some basic laboratory equipment, owners and keepers can carry out their own DIY in-house FEC testing to support their vet in deciding if any further treatment is necessary.

What Laboratory Equipment And Supplies Do I Need for FEC Testing?

How much DIY faecal worm egg counting you choose to do yourself depends only on your level of self confidence, readiness to gain experience and access to the appropriate and readily available laboratory equipment and consumables.

The FEC process divides readily into four stages: recovery of appropriate faecal samples, parasite egg recovery, egg counting, and interpretation of results. Depending on those results, a fifth stage might involve any appropriate veterinary treatment and any necessary changes to pasturing, stabling and hygiene practice.

How Can I Start DIY Animal Faeces Sampling?

SCOPS recommends collecting a representative number of fresh (warm to the touch) faecal samples from your animals. Disposable gloves and hand cleanser are also recommended as the minimum level of protective hygiene. Everything you need to carry out your own hygienic sampling can be found on the Vetlab Supplies Laboratory Consumables pages

What Do I Need To Separate Parasite Eggs from Faeces?

Parasite eggs are less dense than the faecal material that contains them. Left for long enough, a dispersion of faeces in water would allow the eggs to float free of the faecal material. However, this process is too slow to be practical, so gravity needs a little help to speed things along.

Mixing the faeces with a solution that encourages the eggs to float and the faecal matter to sink is made easy with Vetlab Supplies Ready-Made and Bespoke Floatation Solutions.

How Do I Count The Number Of Worm Eggs In A Faeces Sample?

Counting worm eggs sounds like a difficult task. But with a few pieces of the right kit, and a little practice, keepers can become proficient at estimating the worm burden of their animals. This count will equip keepers with sufficient information to approach their vet for advice on the appropriate anti-worm treatment.

Parasite egg counting requires one of the easy to use and economically available microscopes as recommended by Vetlab Supplies. The Vetlab helpline can guide you through the process of selecting and obtaining a microscope appropriate to your need.

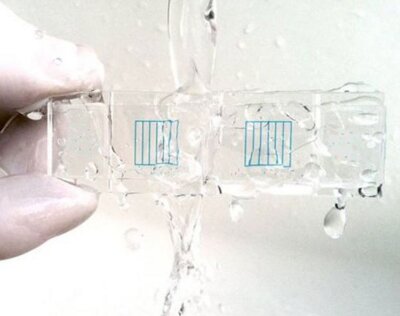

Counting parasite eggs is made easy by the use of the tried and tested McMaster Worm Egg Counting Slide. The McMaster Slide holds a fixed volume of the liquid from the faeces sample. The number of worm eggs in this volume of sample can be counted by viewing the slide under the microscope.

All of the equipment required is available to purchase individually or as part of a complete bespoke kit.

How Do I Know If My Animals Need Veterinary Treatment?

A simple maths formula, calculated from how much of the faecal sample was tested, how much flotation solution was added, and how many eggs were counted on the McMaster slide gives you and your vet a measure of the worm burden for the animal tested.

With this FEC knowledge, you will be able to discuss with your vet the best course of any required treatment and helping prevent the emergence of multi-resistant worm infections in your animals.

To find out more about our range of Bespoke Parasitology Starter kits and the Vetlab McMaster Worm Egg Counting Method visit our website: www.vetlabsupplies.co.uk or call Tel: 01798 874567