Still The Best Protection Against ‘Tracker Dog Disease’ Ehrlichiosis

Environmental change is exposing Britain’s dogs to more and more diseases once confined to warmer Mediterranean and tropical climes. Diseases spread by ‘vectors’ including fleas, mites and ticks pose a special risk. One such disease, Canine Ehrlichiosis, is of growing concern to UK vets and dog owners.

Tracker Dog Disease

Called ‘tracker dog disease’ and tropical pancytopenia in the US, due to its infection of military dogs serving in Vietnam, Canine Ehrlichiosis is also known as canine rickettsiosis or canine haemorrhagic fever. The infection spreads from dog to dog in the saliva of bites from the nymphs of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus.

Acute symptoms of the disease include; fever, anorexia, depression, with longer-term chronic symptoms such as anaemia, weight loss, depression, petechiae, pale mucous membranes and oedema. In the most severe cases, infected dogs may die from massive haemorrhaging, severe debilitation or secondary infections. Some infected dogs show no clinical signs and remain as carriers for many years, but may suddenly develop chronic symptoms.

What Causes the Symptoms?

Canine Ehrlichiosis symptoms may be caused by infection with one of a number of Ehrlichia spp. pathogens including Ehrlichia canis. E. canis is widespread in the warmer parts of many countries including France, Greece, Spain and Italy. In 2013 a Tibetan Terrier in London with no history of foreign travel outside of the UK, or known contact with travelled dogs, was diagnosed with E.canis.

The pathogenic agent of Ehrlichiosis is an intracellular Gram-negative bacteria that penetrates and destroys white blood cells. Ehrlichia bacteria are similar to other pathogenic invaders including Rickettsiacea and Anaplasma spp.

In the last few decades, interest in Ehrlichioses has spread beyond the veterinary profession. In 1986, the first diagnosis of the condition in a human patient indicated Ehrlichia’s zoonotic potential and risk to human health.

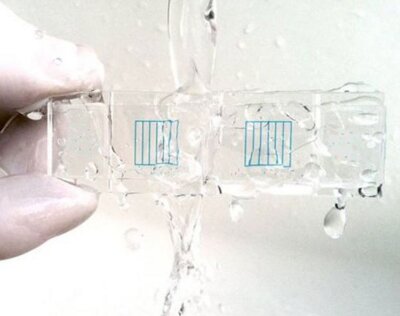

MegaCor FASTest Ehrlichia canis is a is a rapid immunochromatographic screening test for antibodies produced in response to Ehrlichia canis infection. As with other kits in the FASTest veterinary diagnostic range, the all-in-one test kit is simple to use, responds positively with a quick, clear-cut colour-change with a shelf life of up to 24 months even at room temperature storage.

Warm Weather and Parasite Activity

Although there are no current vaccines against Ehrlichia infections, most dogs recover from the acute and subclinical phases. With the approach of warmer weather and increasing parasite activity, preventing canine ehrlichiosis, and other tick-borne diseases including Lymes disease and Borrelia burgdorferi, will best be achieved by avoiding exposure to the tick vector. Your vet will be able to advise on the most suitable tick preventative measures for your dog and lifestyle.

To find out more about our large range of veterinary diagnostic test kits visit our website: www.vetlabsupplies.co.uk or Telephone: 01798 874567